INTRODUCTION

IN ALL FAIRNESS, I should start this book with an apology—not to you, reader, though I don’t doubt that I’ll owe you at least one by the time we get to the end. I owe JavaScript a number of apologies for the things I said to it during the early years of my career—things strong enough to etch glass.

This is my not-so-subtle way of saying that JavaScript can be a tricky thing to learn.

HTML and CSS are tough in their own ways, but we can learn about them piecemeal. They’re simpler in that we type something and it happens: border-radius rounds corners the way we tell it to; a p tag is for paragraphs, full stop.

When I was just starting out with JavaScript, on the other hand, everything I learned seemed to be the tip of a new and terrifying iceberg—a link in a chain of interconnected concepts, each one more complicated than the last—variables and logic and vocabulary and mathematics that I assumed I would never fully understand. When I’d type something, it wouldn’t always mean exactly what it said. If I pasted something into the wrong place, it could anger JavaScript. When I made a mistake, things broke.

If it feels like I’ve just plagiarized the scariest pages of your dream journal and you’ve already thrown this book across the room in horror, take heart: I say all this not to confirm your fears about JavaScript, but to say that I had the same ones. It wasn’t long ago that I was copying and pasting pre-made scripts of dubious quality, then crossing my fingers and hoping for the best as I reloaded a page. An entire programming language seemed like too much to ever fully understand, and I was certain that I wasn't tuned for it. I was a developer, sure, but I wasn't a developer-developer. I didn't have the requisite robot brain; I just put borders on things for a living.

I was intimidated.

You might be in the same place I once was, standing here on the precipice of a hundred-odd pages, waiting to get blindsided by talk of “variable hoisting” and “scope chains” somewhere around page ten. I won’t do that to you, and I won’t talk down to you, either.

JavaScript isn't the easiest thing to understand, and my goal isn’t to cover all of it in this book. I don’t know all of it, and I’m not certain anyone does. My goal is to help you reach what is arguably the most important part of learning any language: the moment when things start to click.

What Even Is JavaScript?

The name itself could be a little confusing. Seeing “Java” in there might conjure up images of ancient browser “applets” or server-side programming languages. When JavaScript first came about back in 1995 (http://bkaprt.com/jsfwd/00-01/), it was originally named “LiveScript”—a nod to the fact that it runs as soon as the browser requests and parses it. But Java was the new hotness back in 1995—and the two languages shared a few syntactical similarities—so for the sake of marketing, “LiveScript” became “JavaScript.”

JavaScript is a lightweight but incredibly powerful scripting language. Unlike many other programming languages, JavaScript doesn’t need to be translated from human-readable code into a form that the browser can understand—there’s no compiler step. Our scripts are sent across the wire at more or less the same time as our other assets—markup, images, and stylesheets—and interpreted on the fly.

While we most frequently encounter it through our browsers, JavaScript has snuck into everything from native applications to ebooks. It’s one of the most popular programming languages in the world, largely because you can find it in so many different environments. JavaScript doesn’t have any strict requirements for where it runs as long as there’s an interpreter to make sense of it, and open-source browsers mean open-source JavaScript interpreters—the part of the browser that parses and executes JavaScript. When developers drop these interpreters into new contexts, we end up with JavaScript-powered web servers (http://nodejs.org) and homemade robots (http://johnny-five.io). We’ll be looking at JavaScript as we encounter it in the browser, but there’s good news if you find yourself feeling particularly mad-scientist-y by the time we’re finished: the syntax you’re learning here is the same syntax you might one day end up using in your JavaScript-powered freeze ray.

The interactive layer

JavaScript allows us to add interaction to our pages as a complement to the structural layer that is markup and the presentational layer that is CSS.

It gives us a tremendous amount of control over a user's interactions with a page—that control even extends beyond the page itself and allows us to alter the browser’s built-in behaviors. You’ve likely encountered a simple example of JavaScript-altered browser behavior more times than you can count: form-input validation. Before a form can be submitted, a validation script loops through all associated inputs, checks their values against a set of rules, and either allows the form submission to go through, or prevents it (FIG 0.1).

With JavaScript, we’re able to build richer experiences for users, like pages that respond to their interactions without needing to direct them to a new page, even when requesting new data from the server. It also allows us to fill in gaps where a browser’s built-in functionality might fall short, work around major bugs, or port brand-new features back to older browsers that lack native support for them. In short, JavaScript allows us to create more advanced interfaces than HTML and CSS could do alone.

What JavaScript Isn’t (Anymore)

Though it gives us a lot of power over browser behavior, it isn’t hard to imagine how JavaScript might get a bad reputation. To render a page unusable with CSS (no pun intended), we have to be explicit about it. body { display: none; } isn’t something that generally makes it into our stylesheets by accident, though I wouldn’t necessarily put it past me. It’s even harder to make a markup mistake that would prevent the page from functioning at all—a strong tag mistakenly left open may not result in the prettiest page ever, but it isn’t likely to completely prevent someone from using it. And when CSS and markup errors do cause major issues, it’s apt to happen in a visible way, so if HTML or CSS completely break the page, we’re likely to see it in our testing.

JavaScript differs there, though. For example: if we include a small script to validate a street address entered into a form input, the page will render just as expected—and when we punch in “5 Address Street” to test it and get no errors, our form validation may seem to be going according to plan. But if we’re not careful about the rules for our validation script, a user with an oddly formatted address could very well be prevented from submitting valid information. For us to test thoroughly, we’d need to try as many strange addresses as we could find, and we’d be bound to miss a few.

Back when the web was younger and the web development profession was brand-new, we didn’t have clearly defined best practices for handling JavaScript enhancements. Consistent testing was all but impossible, and browser support was incredibly spotty. This combination led to a lot of flaky, site-obliterating scripts making their way into the wild. Meanwhile, some of the internet’s more unsavory types suddenly found themselves with the power to influence the behavior of users' browsers, held back only by boundaries that were inconsistent at best and non-existent at worst. This was not, as one might expect, always used for good.

JavaScript caught a lot of flak in those days. It was seen as unreliable, and even dangerous—a shoddily-built popup-window engine lurking somewhere beneath the surface of the browser.

Times have changed, though. The same kinds of web standards efforts that brought us semantically-meaningful markup and sane CSS support have also made JavaScript’s syntax more consistent from browser to browser, and set reasonable constraints around the parts of a browser’s behavior it can influence. At the same time, JavaScript “helper” frameworks like jQuery—built on a foundation of best practices and designed to normalize browser quirks and bugs—now help developers write better, faster JavaScript.

The DOM: How JavaScript Communicates with the Page

JavaScript communicates with the contents of our pages by way of an API named the Document Object Model, or DOM (http://bkaprt.com/jsfwd/00-02/). The DOM is what allows us to access and manipulate the contents of a document with JavaScript. Just like Flickr’s API might allow us to read from and write information to their service, the DOM API allows us to read, alter, and remove information from documents—to change things on the webpage itself.

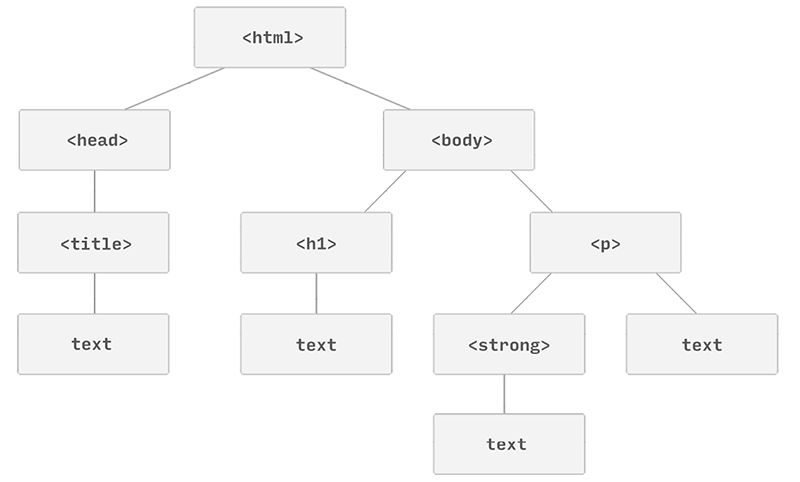

The DOM serves two purposes. The first is providing JavaScript with a structured “map” of the page by translating our markup to a form that JavaScript (and many other languages) can understand. Without the DOM, JavaScript wouldn’t have any sense of a document’s contents. The entirety of the document’s contents—every individual part of our document—is a “node” that JavaScript is able to access via the DOM. Every element, comment, and even snippet of text is a node.

The DOM’s second purpose is to provide JavaScript with a set of methods and functions that allow access to the mapped nodes—fetching a list of all p tags in the document, for example, or gathering up all elements with a class of

.toggle that have a .collapsible parent element. These methods are standardized across browsers, with catchy names like

getElementsByTagName or createTextNode. Having these methods built into JavaScript can lead to a little confusion over where JavaScript ends and the DOM begins, but fortunately that isn’t something we have to worry about just yet.

Let’s Get Started

Over the course of this book, we’ll learn the rules of the JavaScript game as it is played, spend a little quality time wading through the DOM, and pull apart some real scripts to see what makes them tick. Before that, though—before we go toe-to-toe with the beast that is JavaScript—we have to get familiar with the tools of our new trade.

I’m from a carpentry background, and if someone had sent me up on a roof on day one, I’m not sure I would have fared too well—or been around to write any of this in the first place. So in this next chapter, we’ll start getting a feel for the development tools and debugging environments built into modern browsers, and we’ll set up a development environment so we’re ready to start writing some scripts.